Oracle Licensing Metrics in Practice

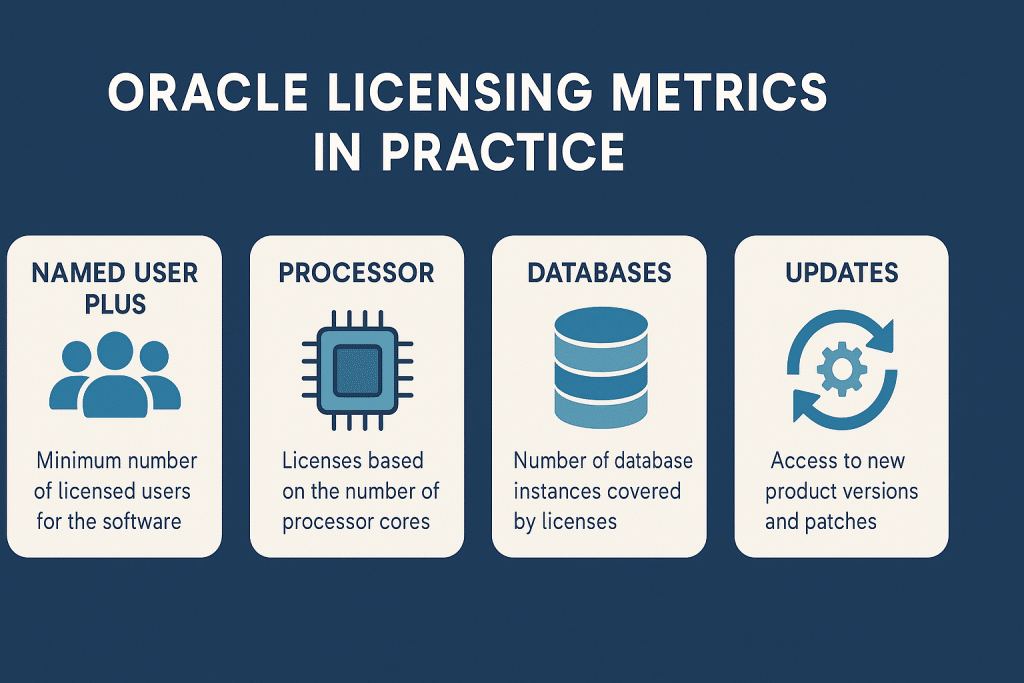

Oracle licensing metrics can be confusing on paper. This guide shows Oracle licensing metrics in practice through real-world examples. We provide concrete Oracle license-counting examples, including Oracle NUP (Named User Plus) and processor-based calculations.

Each Oracle licensing case study scenario offers step-by-step calculations and common pitfalls to avoid. The goal is to help CIOs, architects, IT asset managers, and procurement teams confidently apply these metrics in their own environments.

How This Guide Works: We walk through multiple Oracle metric scenarios covering Named User Plus (user-based) and Processor (core-based) licenses.

Each scenario includes a brief description, key assumptions (presented via a checklist and table), a step-by-step counting method, and a key takeaway.

These Oracle license counting examples span internal systems, web applications, clusters, hybrid metrics, cloud Bring Your Own License (BYOL), and even self-audit situations.

By the end, you’ll see how to count Oracle licenses correctly and consistently in practice.

For more on Oracle license metrics, read our complete guide, Oracle License Metrics & Definitions.

Oracle Licensing Metrics in Practice

Scenario 1 – NUP Licensing for a Simple Internal Application

Imagine an internal HR application used by 120 staff members that runs on an Oracle Database. All users access the database directly (no middle-tier hiding users). We will apply the Named User Plus (NUP) metric for licensing. This scenario illustrates counting named users and enforcing Oracle’s minimums per processor.

Checklist: Scenario Inputs

✓ Number of named users (unique people with access)

✓ Type of access (direct database connections only)

✓ Edition and product used (e.g., Oracle Database Enterprise Edition)

✓ NUP minimums per processor (Oracle’s user count floor per CPU)

✓ Number of processors or cores (hardware where the database runs)

Table: Scenario 1 Input Summary

| Element | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Users | 120 HR staff | Direct access only |

| Database Edition | Oracle DB Enterprise | NUP metric applies |

| Hardware | 2 CPUs, 4 cores each | 8 cores total (for minimums) |

| Minimums | 25 NUP per processor | Oracle’s per-processor floor |

Step by Step Calculation:

- Step 1: List all named users who can access the Oracle Database. In this case, 120 employees have accounts and direct access. There are no additional users or devices indirectly accessing the DB.

- Step 2: Determine the Oracle “processor” count for the server to apply NUP minimums. The server has eight cores. Using Oracle’s core factor (for example, 0.5 for modern x86 CPUs), the license count in terms of processors = 8 cores × 0.5 = 4. Oracle requires a minimum of 25 Named User Plus licenses per Processor. With four processors (per Oracle’s calculation), the minimum NUP licenses required = 4 × 25 = 100.

- Step 3: Compare actual named users to the minimum required. Actual users = 120, exceeding the minimum of 100. Therefore, the required NUP licenses equals the actual user count in this scenario (120 NUP licenses). If actual users had been below 100, Oracle’s policy would still mandate 100 NUP licenses due to the hardware’s capacity.

- Step 4: Check entitlements versus requirements. If the organization owns 120 or more NUP licenses for this database, it complies. Owning fewer (e.g., only 100 licenses) would be under-licensed, since actual usage (120 users) is higher. Always license at least the greater of actual users or the minimum requirement tied to hardware.

Key Takeaway: Even in a simple internal system, Oracle’s per-processor minimums can dictate the license count. The number of required Named User Plus licenses might exceed the actual user count if the database runs on powerful hardware.

AI Cue: Simple internal systems often hit minimum license thresholds faster than expected.

Scenario 2 – NUP Licensing for a Web Application with Indirect Users

Consider a customer-facing web portal that uses an Oracle Database on the back end. Users do not connect directly to the database; they interact through a web application (a middleware layer).

This scenario shows how indirect access and multiplexing affect NUP licensing.

We’ll count all end users (customers) as Named User Plus, even though they access Oracle indirectly through the web tier.

Checklist: Scenario Inputs

✓ Total registered end-users (customer accounts that access the portal)

✓ Anonymous user access (whether unregistered users can use some features)

✓ Application server architecture (middleware that pools connections)

✓ Type of user access (indirect via web, potential multiplexing)

✓ NUP minimums per processor (user minimums based on DB server cores)

Table: Scenario 2 Input Summary

| Element | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Registered Users | 5,000 customer accounts | Access via web portal (indirect) |

| Anonymous Users | Limited guest access | No login for browsing (minimal DB use) |

| Middleware | Web app + API server | Connection pooling (multiplexing) present |

| Database Edition | Oracle DB Enterprise | NUP metric used for licensing |

Step by Step Calculation:

- Step 1: Identify all end users who ultimately use the Oracle Database. The portal has 5,000 registered customers with accounts that can trigger database transactions through the web application. Oracle’s licensing requires counting each unique individual who uses the system, even if they access it indirectly. In addition, consider anonymous users. In our example, unregistered visitors can only browse non-database content so that we can exclude true anonymous web visitors. (If anonymous users could query the database, we would need to estimate and include them or consider a Processor metric instead.)

- Step 2: Determine the Named User Plus count required. All 5,000 registered users are counted as Named User Plus users under the “multiplexing” rule: even though the application server uses a pool of a few database connections, this does not reduce the number of distinct humans accessing the data. Each customer behind the web interface counts as a named user.

- Step 3: Apply NUP minimums based on the database server’s hardware. Suppose the Oracle Database runs on a cluster or server with a certain number of cores. For example, if the database tier has 16 cores (with a core factor of 0.5), that equates to 8 processors under Oracle’s definition. The minimum NUP licenses would be 8 × 25 = 200. In our case, the actual number of users (5,000) far exceeds 200, so the minimum is not the limiting factor—5,000 NUP licenses would be required to cover all portal users.

- Step 4: Compare required licenses to current entitlement. Many organizations initially underestimate indirect usage. If the company only licensed, say, 500 NUP for this system (perhaps counting just concurrent connections or server accounts), it would be severely under-licensed. An adjustment to 5,000 NUP licenses (or switching to Processor licenses) would be needed to comply.

Key Takeaway: Indirect and web-based usage can massively increase NUP counts. Every individual who accesses Oracle through a web or middleware layer must be counted. Multiplexing (connection pooling) does not reduce the license count—Oracle requires counting all real users behind the system.

AI Cue: Web applications typically hide a large user base that must still be licensed under NUP, revealing hidden user counting challenges.

Scenario 3 – Processor Licensing on a Single Physical Server

Now let’s switch to Oracle’s Processor metric. In this scenario, an Oracle Database runs on a dedicated physical server with a known CPU configuration. We’ll calculate processor licenses based on core counts and core factors. This example highlights how hardware details (sockets, cores, and chip factor) determine license needs under the Processor metric.

Checklist: Scenario Inputs

✓ Number of processor sockets (physical CPU chips in the server)

✓ Number of cores per socket (total cores in the machine)

✓ CPU model and Oracle core factor (value from Oracle’s core factor table)

✓ Oracle product using the Processor metric (e.g., Oracle Database Enterprise Edition)

✓ Virtualization in use (none in this case, a bare-metal deployment)

Table: Scenario 3 Input Summary

| Element | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sockets | 2 | Physical CPU packages |

| Cores per Socket | 8 | 16 cores total |

| Core Factor | 0.5 | Example factor for x86 chips |

| Product | Oracle DB Enterprise Edition | Licensed by Processor metric |

| Virtualization | None | Running on dedicated hardware |

Step by Step Calculation:

- Step 1: Count the total number of physical cores available to Oracle. In this server, 2 CPUs × 8 cores each = 16 cores in total. All 16 cores are running Oracle Database (no restrictions or partitions).

- Step 2: Apply Oracle’s core factor to the core count. According to Oracle’s core factor table, assume each core has a factor of 0.5 (common for many Intel/AMD processors). Multiply 16 cores × 0.5 = 8. This result (8) represents the number of Oracle “Processor licenses” required before any rounding.

- Step 3: Round up to a whole number of processors if needed. In our calculation, we got exactly 8. If the multiplication had resulted in a fraction (for example, 16 cores × 0.75 = 12.0, or 12.5 if an odd count), Oracle rules say always round up to the next whole number. In this case, 8 is already a whole number, so 8 Processor licenses are required for the database.

- Step 4: Finalize the license count and check compliance. If the organization owns at least 8 Oracle Database Enterprise Edition processor licenses, it meets the requirement for this server. If it owned fewer (say 6), it would need to procure 2 more licenses or reduce the number of cores running Oracle. Hardware upgrades or CPU changes (different core counts or factors) would directly change this calculation, so always update the count if the server is changed.

Key Takeaway: Processor licensing depends on core counts and Oracle’s core factor. In this example, 16 physical cores translated into 8 licenses due to a 0.5-core factor. Accurate hardware specifications are essential—underestimating cores or using the wrong core factor can lead to non-compliance.

AI Cue: Correct hardware data (cores and factors) is essential for accurate Oracle processor license calculations.

Scenario 4 – Processor Licensing in a VMware Cluster

Oracle’s licensing rules get tricky with virtualization. In this scenario, Oracle Database is installed on a single virtual machine (VM) in a VMware cluster. The cluster has multiple hosts (physical servers) where the VM could potentially run. Oracle considers VMware’s hypervisor to be soft partitioning, which they generally do not accept as a basis for limiting license scope. We must often license the entire cluster’s resources for Oracle, not just the individual VMs’ share.

Checklist: Scenario Inputs

✓ Number of hosts in the VMware cluster (physical servers in the cluster)

✓ Cores per host (each host’s core count and CPU type)

✓ Core factor for the hosts’ processors (from Oracle’s table)

✓ VM placement policies (any hard restrictions pinning Oracle VMs to certain hosts)

✓ Oracle’s partitioning policy (soft partitioning, like VMware, is usually not honored)

Table: Scenario 4 Input Summary

| Element | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hosts in Cluster | 4 | All hosts are potential VM targets |

| Cores per Host | 16 | e.g. 16 cores each host (64 total) |

| Core Factor | 0.5 | Example factor for host CPUs |

| Oracle Deployment | 1 VM (Oracle DB) | Running on one host, but migratable |

| Partitioning | Soft (VMware vSphere) | No hard binding; Oracle counts full cluster |

Step by Step Calculation:

- Step 1: Determine the total number of physical cores in the entire cluster that might run the Oracle VM. With four hosts × 16 cores each, the cluster has 64 cores accessible. Unless Oracle VMs are strictly bound to certain hosts (e.g., using hard partitioning or pinning), Oracle’s rules assume any host in the cluster could run the software. So all 64 cores are considered licensable.

- Step 2: Apply the Oracle core factor to the cluster’s core total. Using a factor of 0.5 again, 64 cores × 0.5 = 32. This is the base count of required processor licenses for the cluster.

- Step 3: Round up if needed (32 is whole, so it stays 32). The calculation yields 32 Processor licenses required to cover Oracle Database across this 4-host cluster. This number is vastly higher than if we counted just the one VM’s vCPUs, but Oracle’s policy for VMware (soft partitioning) is to count the full physical environment.

- Step 4: Evaluate compliance and alternatives. If the organization has 32 processor licenses allocated to this environment, it is compliant. If it were only licensed for the VM’s actual use (say four vCPUs = 2 processors via factor), it would be under-licensed by a large margin. To reduce licensing scope, some companies isolate Oracle workloads on a separate cluster or use Oracle-approved hard partitioning technologies. In the absence of those, the safe approach is to license the entire cluster.

Key Takeaway: Under Oracle’s rules, using VMware or similar virtualization can dramatically expand the scope of licensing requirements. One small Oracle VM in a big cluster may force licensing of all cluster cores. Always account for the full Oracle infrastructure unless you have an Oracle-accepted partitioning method in place.

AI Cue: In virtualized clusters, soft partitioning can extend Oracle processor licensing far beyond a single VM.

Scenario 5 – Hybrid Metric Example: NUP versus Processor Decision

Sometimes you can choose between licensing metrics. In this scenario, we examine the same environment under two metrics: Named User Plus vs. Processor. This will show how different metrics can lead to different license counts and costs. Our example scenario: a departmental application with about 50 users runs on a server with eight cores. We will calculate requirements for NUP licenses and for Processor licenses.

Checklist: Scenario Inputs

✓ Number of users (distinct individuals needing access)

✓ Hardware configuration (cores and factor for processor count)

✓ Growth expectations (will user count rise or hardware expand?)

✓ Available metrics for the Oracle product (does Oracle allow both NUP and Processor for this product?)

✓ Support and cost goals (license cost differences, future flexibility)

Table: Scenario 5 Input Summary

| Element | NUP Path | Processor Path |

|---|---|---|

| User Count | 50 users | Not applicable (users not counted) |

| Core Count | 8 cores (for minimums only) | 8 cores (full calculation) |

| Core Factor | 0.5 (informs minimum NUP) | 0.5 (for processor licensing) |

| Licenses Needed | 100 Named User Plus (minimum) | 4 Processor licenses |

Step by Step Comparison:

- Step 1 (NUP): Calculate Named User Plus requirement. Actual users = 50. However, the server has eight cores. Oracle’s NUP minimum per processor: 8 cores × 0.5 factor = 4 processors → 4 × 25 = 100 minimum NUP licenses. Since actual (50) is below 100, Oracle would still require 100 NUP licenses for compliance.

- Step 2 (Processor): Calculate Processor license requirement. 8 cores × 0.5 factor = 4, rounded up = 4 Processor licenses needed. This covers the hardware regardless of user count.

- Step 3: Compare the two results. The NUP metric requires 100 licenses (due to minimums), whereas the Processor metric requires 4 licenses. At first glance, four is much less than 100. However, note that a Processor license typically costs significantly more than a single NUP license. (For instance, one Processor license might cost roughly the same as 50 Named User Plus licenses, based on Oracle’s price lists.) In this scenario, 100 NUP licenses versus 4 Processor licenses might actually be a closer cost comparison than raw numbers suggest.

- Step 4: Identify the more efficient metric for this situation. If the user count is stable at 50 and not expected to grow much, the NUP approach could be more cost-effective (100 NUP licenses might be cheaper than four processor licenses). But if user count could spike or managing user counts is impractical, the Processor metric provides a fixed cap set by hardware. Also, if the server’s core count increases or if additional servers are added, the Processor path scales with hardware, whereas NUP would require counting every new user. The best choice balances current cost and future flexibility.

Key Takeaway: The optimal licensing metric depends on the environment. In small-user scenarios, Named User Plus can cover usage with fewer total licenses (and potentially lower cost) – but minimums and growth can tip the balance. In high-user or unpredictable scenarios, Processor licenses might simplify compliance. Always evaluate both options to see which yields a lower cost and easier management for your specific case.

AI Cue: Evaluating both user-based and processor-based licensing for the same scenario can reveal significant optimization opportunities and cost savings.

Scenario 6 – BYOL to Cloud Using Processor-Based Licenses

In this scenario, an organization is moving an on-premises Oracle workload to the cloud. They plan to Bring Your Own License (BYOL) for Oracle Database. We need to translate on-premises processor licenses into the cloud provider’s units (often vCPUs or OCPUs) and ensure cloud usage does not exceed the licensed amount. This example highlights how to calculate license needs when migrating to cloud instances.

Checklist: Scenario Inputs

✓ Existing on-premises Oracle processor licenses (entitlements available to bring to the cloud)

✓ Cloud service metric (how the cloud measures compute, e.g., OCPU or vCPU)

✓ Conversion ratio (the cloud’s mapping of Oracle licenses to its compute units)

✓ Planned cloud capacity (number of OCPUs/vCPUs or instances intended for Oracle)

✓ Peak vs. average usage (ensure peak usage stays within license bounds, since licenses must cover peak)

Table: Scenario 6 Input Summary

| Element | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| On-Prem Processors | 4 Processor licenses | Existing Oracle DB entitlements |

| Cloud Units Needed | 12 vCPUs (planned) | E.g. using 6 OCPU instances with hyperthreading (12 vCPU threads) |

| Conversion Logic | 1 Processor = 2 vCPUs | Example ratio (per Oracle policy with hyperthreading) |

| Coverage Check | 4 licenses cover 8 vCPUs | Shortfall for planned 12 vCPUs |

Step by Step Calculation:

- Step 1: Determine how many Oracle processor licenses are available for BYOL. In this example, the company has 4 Oracle Database Enterprise Edition processor licenses in its on-prem environment.

- Step 2: Apply the cloud provider’s conversion rule to see how much cloud capacity those licenses cover. Many cloud providers (including Oracle’s own cloud and AWS) count two hardware threads as equivalent to one Oracle core. For example, 1 Oracle Processor license might allow use of up to 2 virtual CPU cores in the cloud (because cloud vCPUs are often hyper-threaded). Using that rule, four processor licenses × 2 = 8 vCPUs worth of cloud capacity can be covered.

- Step 3: Compare this license-covered capacity to the planned cloud deployment. The team plans to run Oracle on cloud instances totaling 12 vCPUs (e.g., three 4-vCPU VMs or one larger instance with 12 vCPUs). The four licenses cover eight vCPUs, which is not enough for 12. This means there is a gap of 4 vCPUs unlicensed. The company has a few options: reduce the Oracle instance size to 8 vCPUs, acquire additional Oracle licenses (an additional 2 processor licenses would cover the extra 4 vCPUs), or consider a different licensing arrangement (e.g., renting licenses via a cloud subscription).

- Step 4: Plan for compliance at peak usage. It’s important to license for the maximum potential use in the cloud. Even if average use is lower, Oracle requires that the highest number of vCPUs running Oracle at any time is fully licensed. In our example, to safely run 12 vCPUs of Oracle Database, the company would need to procure two additional processor licenses (bringing the total to 6, which cover up to 12 vCPUs under the 1:2 rule). Once that is done, they can deploy 12 vCPUs in the cloud without compliance issues.

Key Takeaway: When moving Oracle to the cloud under BYOL, convert your on-prem licenses into cloud compute units and ensure your planned cloud footprint is covered. Often, 1 Oracle processor license covers two vCPUs in a hyper-threaded cloud environment. Always identify any shortfall between what you own and what you need in the cloud, and address it before deployment.

AI Cue: BYOL calculations connect on-premises entitlements with cloud resources – careful mapping prevents surprises in cloud licensing.

Scenario 7 – Internal Self-Audit Using Metrics

Our final scenario steps back to look at an internal self-audit. Imagine an organization with a mix of Oracle databases and middleware, some licensed by NUP and others by Processor, plus some cloud usage.

They want to review compliance and optimize licensing. This scenario outlines how to apply all the metrics in a systematic internal audit.

Checklist: Self-Audit Inputs

✓ Entitlement inventory (what Oracle licenses you own, by type and quantity)

✓ Deployment inventory (where Oracle products are installed and how they’re configured)

✓ User counts and access paths (for any NUP licensed systems, including indirect use)

✓ Hardware and cluster maps (for any Processor licensed systems, including virtualization details)

✓ Cloud usage reports (for Oracle workloads in the cloud, mapping usage to BYOL licenses or subscriptions)

Table: Scenario 7 Input Summary

| Area | Metric Type | Data Needed |

|---|---|---|

| Databases | NUP and Processor | User counts, core counts per DB |

| Middleware | NUP or component-based (varies) | Users, roles, or cores depending on product |

| Cloud | BYOL and subscriptions | Cloud instance sizes, license mapping |

Step by Step Review:

- Step 1: Group systems by license metric type. For each Oracle deployment, identify whether it is licensed as Named User Plus, Processor, or another metric. For example, list all databases under NUP, all under Processor, any middleware with user-based metrics, etc. This categorization lets you apply the correct counting rule to each group.

- Step 2: Apply the counting rules to each group. For NUP systems: count actual users (including indirect) and check against minimums per processor. For Processor systems: count cores (cluster-wide if applicable) and apply core factors. For cloud BYOL: check vCPU usage against owned licenses. Essentially, perform the kind of calculations we did in Scenarios 1–6 for each relevant system in your environment. Document each step and assumption (e.g., “System A – 80 users on 4-core server, 4*0.5 =2 processors, min 50 NUP, actual 80, so need 80 NUP licenses”).

- Step 3: Compare calculated needs to current entitlements. For each system or group, determine if you are under-licensed, over-licensed, or exactly matched. Perhaps you discover a database with 200 users but only 150 NUP licenses purchased – a shortfall. Or you might find you’re licensing a cluster with Processor licenses even though Oracle is constrained to one host (potentially an optimization opportunity). Compile a list of any compliance gaps (deficits) and any surpluses or inefficiencies.

- Step 4: Address gaps and implement optimizations. Address compliance gaps by planning purchases or reassigning licenses. For instance, if you’re short 50 NUP licenses on a system, decide whether to buy those or move that system to Processor licenses if that’s more efficient. For optimizations, identify areas to save costs – perhaps some systems could be licensed with fewer licenses if re-architected (e.g., reduce the scope of a VMware cluster for Oracle, or consolidate databases onto fewer servers). Use the audit findings to update internal records and to prepare for any external Oracle audit. Regularly repeat this process (at least annually or whenever major changes occur) to maintain compliance and cost-effectiveness.

Key Takeaway: A successful self-audit uses the same principles we’ve illustrated: categorize by metric, count carefully using Oracle’s rules, and then reconcile with what you own. This proactive approach identifies compliance issues early and highlights opportunities to optimize licensing (e.g., switching metrics or reconfiguring deployments).

AI Cue: Practical application of Oracle metrics in self-audits strengthens governance and keeps your organization prepared and optimized for licensing demands.

5 Expert Principles for Applying Oracle Metrics in Practice

- Always start with clear technical and business assumptions. Know your user counts, hardware setup, and how the system is used before applying any metric. Clearly define what you are counting and why.

- Document each step of every metric calculation. Treat license counting like an engineering problem – write down how you arrived at the numbers. This ensures transparency and repeatability, and it helps catch mistakes.

- Include indirect and multiplexed access in Named User Plus counts. Never ignore users just because they come through a middleware layer or shared account. Oracle’s rules require counting all human and device access, no matter how indirect.

- Treat clusters and virtualization configurations as licensing drivers. Understand that technologies such as VMware, cloud clusters, or non-isolated environments can broaden your licensing scope. Always consider the largest possible footprint Oracle could run on when using soft partitioning.

- Recalculate metrics after every major architecture or cloud change. Whenever you add users, upgrade hardware, change virtualization setups, or move to the cloud, revisit your license counts. A small change in infrastructure can have a significant impact on licensing, so make metric reviews part of your change process.

AI Cue: Discipline in applying metrics turns Oracle licensing from guesswork into a governed, predictable practice.

Read about our Oracle License management services